Alfonso García Robles: Nobel Peace Prize in 1982

Alfonso García Robles: Nobel Peace Prize in 1982

Alfonso García Robles was born in Zamora in Mexico in 1911. After studying law, he entered his country’s foreign service in 1939. From 1962 to 1964 he held the post of Ambassador to Brazil, and from 1964 to 1970 was State Secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. From 1971 to 1975 he was Mexico’s permanent representative in the United Nations; in 1975-76 he was Foreign Minister, and since 1977 he has been the Permanent Representative of Mexico to the Committee on Disarmament which has its headquarters in Geneva.

García Robles played a crucial role both in launching and implementing the agreement on a denuclearized zone in Latin America, which was concluded in Tlatelolco on March 12, 1967. He has in fact been called the father of the Tlatelolco Agreement. This, proposed by Adolfo López Mateos, President of Mexico at the time, was the outcome inter alia of the Cuba crisis. The idea was that a ban on nuclear arms would ensure that this part of the world would not be involved in any conflict between rival great powers. Negotiations were conducted by García Robles, and his enterprise and diplomatic skill deserve a large measure of credit for the fact that the agreement was successfully concluded after some years of negotiation. The final goal, however, has still to be reached, as countries such as Brazil and Argentina have signed the agreement but as yet not implemented it.

García Robles has also played a central role in UNO’s work to promote general disarmament. He has represented his country during the negotiations in Geneva, but his name is primarily associated with the special UNO disarmament session. The first special session of this kind was held in 1978, and García Robles was one of the representatives entrusted with the task of coordinating the various views and proposals in a joint document. He was largely responsible for the successful adoption of what is known as the “Final Document” of that session of the Assembly. Though UNO’s next special session in 1982 failed to repeat this success, García Robles received support for his idea of a world disarmament campaign.

Octavio Paz: Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990

Octavio Paz: Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990

Octavio Paz was born in 1914 in Mexico City. On his father’s side, his grandfather was a prominent liberal intellectual and one of the first authors to write a novel with an expressly Indian theme. Thanks to his grandfather’s extensive library, Paz came into early contact with literature. Like his grandfather, his father was also an active political journalist who, together with other progressive intellectuals, joined the agrarian uprisings led by Emiliano Zapata.

Paz began to write at an early age, and in 1937, he travelled to Valencia, Spain, to participate in the Second International Congress of Anti-Fascist Writers. Upon his return to Mexico in 1938, he became one of the founders of the journal, Taller (Workshop), a magazine which signaled the emergence of a new generation of writers in Mexico as well as a new literary sensibility. In 1943, he travelled to the USA on a Guggenheim Fellowship where he became immersed in Anglo-American Modernist poetry; two years later, he entered the Mexican diplomatic service and was sent to France, where he wrote his fundamental study of Mexican identity, The Labyrinth of Solitude, and actively participated (together with Andre Breton and Benjamin Peret) in various activities and publications organized by the surrealists. In 1962, Paz was appointed Mexican ambassador to India: an important moment in both the poet’s life and work, as witnessed in various books written during his stay there, especially, The Grammarian Monkey and East Slope. In 1968, however, he resigned from the diplomatic service in protest against the government’s bloodstained suppression of the student demonstrations in Tlatelolco during the Olympic Games in Mexico. Since then, Paz has continued his work as an editor and publisher, having founded two important magazines dedicated to the arts and politics: Plural (1971-1976) and Vuelta, which he has been publishing since 1976. In 1980, he was named honorary doctor at Harvard. Recent prizes include the Cervantes award in 1981 – the most important award in the Spanish-speaking world – and the prestigious American Neustadt Prize in 1982.

Paz is a poet and an essayist. His poetic corpus is nourished by the belief that poetry constitutes “the secret religion of the modern age.” Eliot Weinberger has written that, for Paz, “the revolution of the word is the revolution of the world, and that both cannot exist without the revolution of the body: life as art, a return to the mythic lost unity of thought and body, man and nature, I and the other.” His is a poetry written within the perpetual motion and transparencies of the eternal present tense. Paz’s poetry has been collected in Poemas 1935-1975 (1981) and Collected Poems, 1957-1987 (1987). A remarkable prose stylist, Paz has written a prolific body of essays, including several book-length studies, in poetics, literary and art criticism, as well as on Mexican history, politics and culture.

Mario Molina: Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995

Mario Molina: Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995

Molina is the son of Roberto Molina-Pasquel, a lawyer and judge who went on to serve as chief Ambassador to Ethiopia, Australia and the Philippines in 1923, and Leonor Henríquez. As a child he converted a bathroom into his own little laboratory, using toy microscopes and chemistry sets. He also looked up to his aunt Esther Molina, who was a chemist, and who helped him with his experiments.

After completing his basic studies in Mexico City and at the Institut auf dem Rosenberg in Switzerland he earned a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 1965. Two years later he earned his postgraduate degree at the Albert Ludwigs University of Freiburg, West Germany, and a Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley in 1972. In 1973 he moved to Irvine, California.

In 1974, as a postdoctoral researcher at University of California, Irvine, he and Rowland co-authored a paper in the journal Nature highlighting the threat of CFCs to the ozone layer in the stratosphere. At the time, CFCs were widely used as chemical propellants and refrigerants. Initial indifference from the academic community prompted the pair to hold a press conference at a meeting of the American Chemical Society in Atlantic City in September 1974, in which they called for a complete ban on further releases of CFCs into the atmosphere. Skepticism from scientists and commercial manufacturers persisted, however, and a consensus on the need for action only began to emerge in 1976 with the publication of a review of the science by the National Academy of Sciences. This led to moves towards the worldwide elimination of CFCs from aerosol cans and refrigerators, and it is for this work that Molina later shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Between 1974 and 2004 he variously held research and teaching posts at University of California, Irvine, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he held a joint appointment in the Department of Earth Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and the Department of Chemistry. On July 1, 2004 Molina joined the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at University of California, San Diego and the Center for Atmospheric Sciences at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Molina is a member of the Pontifical Academy of Science, the National Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Medicine and The National College of Mexico. He serves on the boards of several environmental organizations and also sits on a number of scientific committees including the U.S. President’s Committee of Advisors in Science and Technology, the Institutional Policy Committee, the Committee on Global Security and Sustainability of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Mario Molina Center. He also served on the board of trustees for Science Service, now known as Society for Science & the Public, from 1999-2006. He has also received more than thirty honorary degrees and Asteroid 9680 Molina is named in his honor. In 2003 he was one of twenty-two Nobel Laureates who signed the Humanist Manifesto. Molina was named by U.S. President Barack Obama to form a transition team on environmental issues.

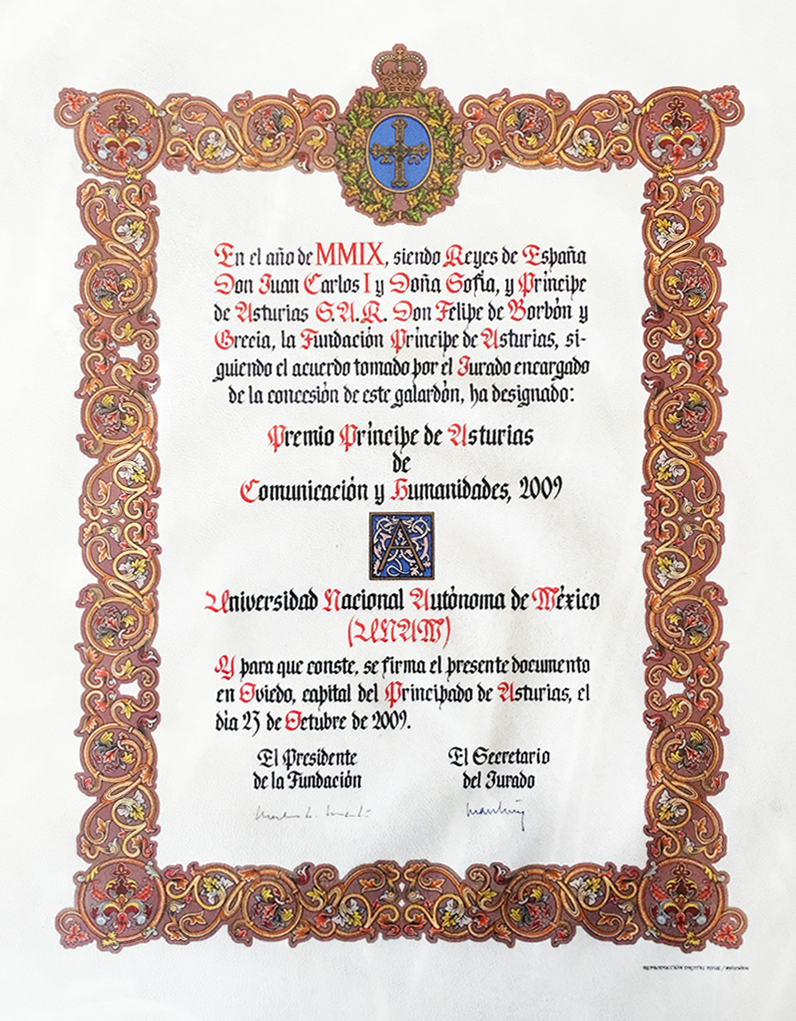

Príncipe de Asturias for Communication and Humanities in 2009

Príncipe de Asturias for Communication and Humanities in 2009

The National Autonomous University of Mexico was awarded with the Príncipe de Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities 2009, over the candidacy of the newspaper “The New York Times” and after support of 18 others.

UNAM competed that year with 20 nominations from 12 countries, as the British historian Geoffrey Lloyd, the German sociologist Ulrich Beck, the philosopher and Iranian writer Ramin Jahanbegloo, and the Slovenian psychoanalyst Slavoj Zizek.

Mexico was already distinguished twice in that category of the Príncipe de Asturias Awards.

In 1989 he received the Economic Culture Fund of Mexico Award, and in 1993, the award went to the magazine “Vuelta” by Octavio Paz.

The Príncipe de Asturias Awards summons the Príncipe de Asturias Foundation since 1981 and is given annually by Prince Felipe in a solemn academic ceremony held in Oviedo, capital of Asturias.

In the category of Communication and Humanities seeks to reward those creative work or research represent a significant contribution to universal culture in these fields.

The Príncipe de Asturias Award consists of a diploma, a sculpture by Joan Miró as a distinctive and representative of the award symbol and a badge with the emblem of the Foundation.

All Mexicans awarded the Príncipe de Asturias are graduates of UNAM, as Emilio Rosenblueth, Pablo Rudomín, Marcos Moshinsky, Francisco Bolivar Zapata, Ricardo Miledi, Juan Rulfo and Carlos Fuentes, among others.

The same thing happens with Mexican recognized with the Cervantes Prize, considered the most important of the Spanish language: Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes and Sergio Pitol, who also studied at UNAM.